The debate of subsidy rationalization is now hitting the news headlines, not without a reason. Retail sugar prices were raised by 20 sen on 10th May, the third such increase in under a year. The subsidy removal will reportedly enable the government to save RM 116.6 million in a year, freeing resources for more useful expenditure (Malaysiakini 11 May 2011).

The debate of subsidy rationalization is now hitting the news headlines, not without a reason. Retail sugar prices were raised by 20 sen on 10th May, the third such increase in under a year. The subsidy removal will reportedly enable the government to save RM 116.6 million in a year, freeing resources for more useful expenditure (Malaysiakini 11 May 2011).

The government has been saying that Malaysia cannot afford subsidy assistance for its people forever. In 2009 alone, the government reported that it spent RM 74 billion on subsidies for the people. Hence, Malaysians have been enjoying artificially low food and necessities prices compared with our regional peers. It has rendered Malaysia’s economy comparatively uncompetitive and vulnerable to price shocks.

Yet in the same vein, the government has been accused of footing a RM 19 billion subsidy in gas prices for independent power producers (IPPs) and TNB, although the Energy, Green Technology and Water Minister denies this (BERNAMA, 24 May). In fact, 60 percent of the power in Malaysia is generated by the IPPs, which means an estimated RM 11 billion goes to selected corporations’ bottom line.

Misplaced priorities

Based on ballpark calculations of the Auditor General report for 2009, the government lost almost RM 28 billion due to leakages and wasteful spending. Indeed, it is a common knowledge that many big government projects are not done via open tender basis but on a direct negotiation basis. As a result, there is plenty of room for corrupted practices and wasteful spending. The many white elephants throughout the country attest to this contention.

The argument for cutting subsidies is a logical and rational one. However, the people need to be able to earn good and reasonable income to overcome the effects of price hikes resulting from the subsidies cut. Many Malaysians are ill-equipped to handle the price hikes as their purchasing power is relatively lower than many countries.

The argument for cutting subsidies is a logical and rational one. However, the people need to be able to earn good and reasonable income to overcome the effects of price hikes resulting from the subsidies cut. Many Malaysians are ill-equipped to handle the price hikes as their purchasing power is relatively lower than many countries.

According to the Swiss Bank UBS 2010 Price and Wages Report, “residents in Kuala Lumpur have only 33.8 percent purchasing power of their counterparts in New York, 42 percent that of London, 33.7 percent that of Sydney, 32.6 percent that of Los Angeles and 31.6 percent Zurich.” (The Malaysian Insider, 19 April).

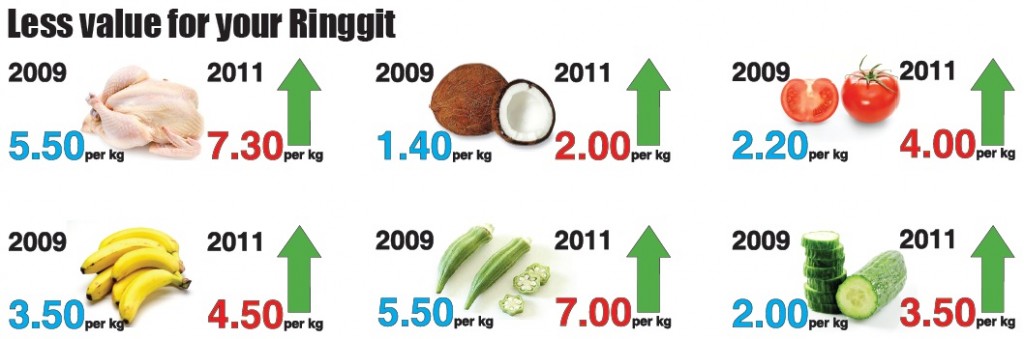

Malaysians as a whole pay much higher for food, cars and telecommunication items as a percentage of their income.

The dwindling real ringgit incomes of many Malaysians have seen them come to depend on personal loans and credit to finance purchases for necessities. Household debt in Malaysia has now reached 80 percent of GDP, the second highest in Asia. More than 20 percent of the RM 581 billion household debt is now held in cars, an asset that depreciates over time (The Malaysian Insider, 19 April). Where has the government’s oft-repeated aim to solve the country’s transportation woes gone to?

Stagnant incomes

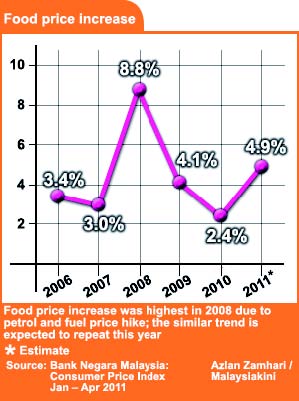

Malaysians’ wage earners have been facing a suffocating situation in the form of rising food and necessities prices and dwindling wage rate in real ringgit terms. Food prices have been rising on an average of 4.3 percent since 2006, while the wage rate has registered a paltry 2.6 percent increase from 2001 to 2010.

The 2007-2008 petrol fuel hikes saw food prices spiralling to frightening levels, even causing riots in many countries around the world. It is an observable phenomenon that a corresponding ringgit increase in petrol prices will bring a bigger price increase effect on the production and distribution chains of goods and services.

To tackle the subsidy issue, PEMANDU (the government’s agency in charge of rationalising the subsidies expenditure) has proposed that the petrol prices be increased systematically so as to cushion the effect of the subsidy removal.

To tackle the subsidy issue, PEMANDU (the government’s agency in charge of rationalising the subsidies expenditure) has proposed that the petrol prices be increased systematically so as to cushion the effect of the subsidy removal.

In particular RON 95 is to be increased from RM 1.95 in 2010 to RM 2.60 by 2015, representing a 33 percent hike. Will the typical wage earner be able to cope with that quantum of hike considering that his income will basically be stagnant based on past precedence in the last decade? The government’s misplacement of priorities seems evident in its selective implementation of subsidies cuts.

One of the reasons for the income level stagnating in Malaysia is the slowing down of private investments. Since 1998, Malaysia has annually obtained less than USD 4 billion in net foreign direct investments (FDI). In fact from 2006 to 2009, Malaysia had negative net FDI flow (UNCTAD World Investment Report 2009).

Not only are foreign investors shunning us for other destinations, even local private investors are deserting our shores for our regional peers. Private investments in the country plunged from about 24 percent of the country’s GDP for the period of1988-1997 to 12 percent in 2008. With the flight of investments too goes the high paying jobs.

Related to the dwindling investments is the exodus of the country’s brightest and talented workers. According to the World Bank report on Malaysia titled “Malaysia Economic Monitor April 2011 : Brain Drain”, there are an estimated 1 million Malaysians working outside the country. Many of them are occupying high positions or important jobs in their countries of abode. The same report also mentioned the fact that the current innovation practices and brain drain has cost Malaysia to lose out on nearly four times the amount of potential FDI in the last three years.

Solutions for the brave

Malaysia’s structural weaknesses have been pointed out and articulated succinctly by the National Economic Action Council (NEAC) and many other commentators. This piece is a mere rehash of some of their more salient arguments.

The necessity to redress the economic imbalance between the have-nots and haves means that there has to be a fairer and more appropriate affirmative action for the deserving poor, not the current single-race-favouring New Economic Plan (NEP). The primary focus should be looking at providing the necessary education and training for the poor to get ahead, not opiate them with the perpetual crutches of quotas.

The subsidy rationalisation program, while necessary, should be restructured. Gas fuel for all power producers should be supplied at market prices and consumers be charged the competitive market rate. To cushion the impact for the poor and to encourage prudent usage, residential users should be given free electricity for the first block of wattage and any higher usage is charged accordingly. On the other hand, industrial and commercial users will have to improve on fuel saving measures in order to compete with other countries.

Finally, retaining our talent should be one of the most important priorities of the government. The yearly fiasco of the misallocation of scholarships by the Public Service Department (PSD) is wearing down the patience of the public. The government’s commitment to retain the country’s brightest children should be seen, not just heard. So should all its restructuring efforts. -The Rocket